August 15th, 2025

A few days ago, when the weird schedule and sleep deprivation truly hit me, I was very ready to be home and was excited for the steam back to port. Now that the day has come, first light has dawned, and last few hours on this beautiful ocean are fleeting, I’m struggling to accept that we’re going back, I want to stop time.

Jason made me a liar this morning. I woke up to the second half of the final dive of this Leg. From J2-1696 to J2-1723, each of every single 27 dives offered something new and piqued my intrigue in a unique way. The conditions this morning were non-ideal for diving. The large amounts of particulates in the water clouded the screen as they quickly rushed past the camera carried by the current. It almost looked apocalyptic what the Jason team was working through – like the ocean was testing us on what we had learned throughout this journey.

Several hours later, I was helping with sampling in the lab. In anticipation of arriving at port around 1000, I was constantly looking out of the portlight providing the room with most of its light. Rocks suddenly lined the bottom of the thick metal circle. We were back. We had reached a good stopping point in our sampling, so we cleaned up and raced to the bow. A cool mist greeted our faces as we climbed the stairs to the deck—the weather was significantly worse welcoming us back to port compared to the sendoff we had twelve or thirteen days ago. The faint silhouette of the Newport Bridge was a happy sight. Now that we were in such proximity to land, my mood shifted. I had forgotten what the land and the trees smelled like and was baffled by the elevation so close to me after seeing a flat horizon for so long. Much of the crew that wasn’t helping with the ship, was on the bow watching the sealions frolic in the water and hearing the birds chirp. What a lovely welcoming party.

This has absolutely been the opportunity of a lifetime. What a privilege it has been to participate in such an incredible operation. So much of this world has been seen and explored, so much is known, but to get to experience the wonder of discovery and of the unknown in this part of the ocean has made me fall in love with this field and planet all over again. My heart is so full, my mind in such awe, and my body very tired, but it was all so worth it. Through the low days full of cereal-based meals and seasickness, to the highest of days filled with hydrothermal vents and hagfish, I wouldn’t trade a second of it for anything. I was a TA for a class that Dr. Kelley taught this past winter at the University of Washington, which is what convinced me to apply for this opportunity. She must’ve said that this was a life-changing experience every other class period and now, after being given this incredible chance to share this journey, I wholeheartedly agree with her.

August 14th, 2025

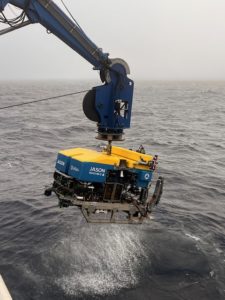

Drama swarmed the ship once again late last night. While attempting to deploy Jason with a heavy package in somewhat rough conditions, the changes in sea surface height (SSH) due to passing swells would give slack in the fiberoptic cable attaching Jason to the ship, then quickly snap back to high tension at the peak of the swell. I had looked away for maybe five seconds when a plethora of gasps was voiced from the Jason team. I looked up and saw the fiberoptic cable snap up from beneath and in front of Jason, caught on a camera that should never see the cable. “Standby.” The pilot noticed that the brow cam, a critical camera angle for dives, had gone dark but was still receiving power. The camera hadn’t fallen off, but it underwent some amount of damage and potentially relocation. An engineer noticed the sudden onset of strange-looking bubbles. Oil had begun leaking from an unknown location, likely from electronics. The winch ripped into action, quickly recovering Jason from its relatively shallow depth and placed it on deck. The dive was cancelled, and I was exhausted from a rather unrestful couple of days. In peak curiosity, I desperately needed to go to bed.

I woke up in the morning to the beginning of a dive. They fixed it all in a short eight hours. I’m continuously impressed by the resilience and brilliance of those onboard this ship, it’s truly inspiring. I settled into the Sealog chair for my shift and got comfy, as this would be one of the most intensive dives I’ve stood watch for. With the loss in time due to repairs, they had decided to combine the previously planned two dives into one large, eight-hour dive. Mostly comprised of deploying new instruments and recovering old instruments, there were several moments of pure wonder. From a crab squaring up as Jason gently touched down on the seafloor next to it, to a methane seep that had suddenly become incredibly active since a couple of days ago, there was no shortage of inspiration, even on somewhat repetitive and patience-testing dives. Flying through clicking buttons and following along with the pilot, the shift was over before I knew it, interrupted briefly for breakfast which included the most heavenly, homemade doughnuts—what a treat this morning was.

The start of my evening shift was slow but ended with flagging the last deep profiler that would be picked up by R/V Sally Ride in the coming weeks. On my way to the van, I noticed a buoy in the water. This quickly caught my attention since we haven’t seen anything but water and the contents of this ship for the past two weeks (almost). It looked very strange. My eyes slowly wandered up to the horizon where they were greeted by grey masses filling the space between the water and the sky. Land. What a novel concept. After spending so much time away from it (as far as my experience goes), I wasn’t expecting this sight, so it took my breath away for a moment. I had to take a second to admire the distant, mountainous Oregon coastline dancing in the mist of the evening. This might have been my last shift—if not, it was my last shift standing a Jason dive. What a bittersweet feeling.

August 13th, 2025

Today offered another set of calm shifts, with my morning on standby waiting for weather to clear up and my evening shift consisting of a couple more maintenance dives. We started the day at Southern Hydrate Ridge but received a notification after breakfast that the science pod on a shallow profiler that was deployed a couple of days ago at Slope Base needed to be recovered for repairs. A transit back out there started soon after the news. Just after I woke up from my morning sleep, the crew was crowded on deck retrieving the pod that was cut loose from the profiler and had floated to the surface. We had a tour of the bridge today which rounded out the main locations of the ship that we were able to tour around. The wrap-around windows at this tall point on the ship were very enjoyable and it was interesting to see how all the electronics worked together to allow the ship, the science, and Jason team to do everything they do.

Since today was a bit of a quiet workday, I’ll take today’s blog post to talk about some of the finer, background details about my first time at sea. First, the challenges of working out on a ship. I boarded this cruise almost two weeks ago knowing I had to continue training for the 200-mile relay race I will be running in early September with twelve other people. The gym on board is thankfully equipped with a treadmill, which I’ve been trying to use whenever conditions allow (weather, other people, transit, etc.). However, the first time I went to use it, I quickly realized that I was in for a very strange time. The best way I can think of to explain it is being put on an extremely hilly path, having to run at a fixed pace, while blindfolded. Despite the entertainment it provided, it became tiring quickly even in the calmest of seas, but I’m hoping those conditions will count for something in my training progress. This was an experience I wasn’t expecting to have, but one I won’t forget.

The next chore that came along was laundry. I was putting this off as long as possible but was pleasantly surprised by the situation given I had no idea what to expect for doing laundry at sea. I was able to time it so I was the only one starting my laundry at the time. The washer was quick, and the dryer was effective, despite having to guess how long it would take. I climbed and descended many flights of stairs to continuously check on the dryer’s progress, but it was overall a very positive first load of laundry at sea. It’s such a small task but felt accomplishing for some reason, I almost feel like I need a shirt that says, “I survived doing laundry in the middle of the ocean.” It was so incredibly refreshing to have warm, clean clothes at the end of a long day.

I’m counting down the days until I can take a shower on a floor that isn’t moving beneath me but am dreading sleeping in a bed that doesn’t rock me to sleep. It’s funny how the same motion can be both a nuisance and a gift in different situations. Growing more tired by the minute, I think that’s enough for today’s strange combination of blog topics, time to retire to the berth that I have come to love dearly.

August 12th, 2025

During my pre-shift debrief, I found out that we had once again had a power issue this morning, but because of a much weirder reason this time. I was informed part of the ship went dark for a brief period because a massive hoard of krill got sucked up into the intake and clogged the system, causing one generator to shut down. Since krill don’t operate on the R/V Atlantis’ schedule, the team had decided to move away from the area in hopes of waiting out what was lovingly deemed the “Krill-Mageddon”. This readjustment in the schedule took up most of my morning shift so I decided to start on a puzzle which left me questioning why I hadn’t started it sooner, it offered lots of entertainment for many throughout the day. A couple of hours later, a word was spoken which had everyone awake out on the deck. “Whales”. We all rushed out to the bow where we were almost immediately greeted by nearby spouts of mother and calf fin whales (likely). Hearing their breaths and admiring the subsequent water vapor glistening in the freshly risen sun was such a beautiful way to start the day. They slowly swam towards the stern of the ship, where we realized they were headed towards a larger pod located off the starboard side, likely capitalizing off the krill that had caused us so much trouble just hours ago.

I settled in for my morning nap after my shift but awoke to some of the most intense movements the ship has undergone so far on this trip, we were transiting once again. I could tell from my berth that we were headed south based on the previous direction of the waves and the up-and-down motion that was tossing me out of bed. Our student meeting time fell during the transit time which was a little inconvenient since I couldn’t focus my entire attention on the talk as I was battling some mild seasickness. We had the pleasure of chatting with Dana Manalang today, an electrical engineer from the Applied Physics Laboratory (APL). She gave us her backstory, talked about her passions, current projects, and future goals. She has been involved with developing and advancing technology in the Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (AUV) space and is hoping to contribute to a global network of these instruments used for easy data collection in the future. Towards the end of the meeting, the ship had calmed atop the waves which signaled we were approaching station.

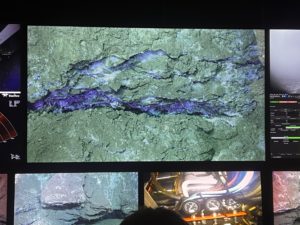

We reached Southern Hydrate Ridge once again and quickly began the scientific survey of the methane seeps below us. I quickly became fascinated with the hydrate and dynamic bacterial mats concentrated around the cracks in the seafloor letting out a steady stream of bubbles. I know so little about those environments so I’m leaning towards doing my project on these areas to learn more about what they are and their ecological role. Hagfish and rockfish were the main animal-based sights, which was very exciting given my fascination with hagfish and their potent slime. An occasional crab or skate sighting always generated some gasps and comments throughout the control van. Then, the most exciting question was posed— “who wants to drive Jason?” Silence fell over the van as everyone thought the pilot was joking. He was not, and we all took turns flying the ROV over the seafloor with smiles plastered on all our faces. Words can’t describe what I was feeling at that moment. A plethora of emotions swarming me, I guided Jason over brittle stars and rocks towards the ship. What an incredible opportunity offered by the team, it will be a truly cherished memory.

We finished off the day by going up to the bow for some stargazing. In hopes of catching some action from the meteor shower, we all waited in darkness as our eyes slowly adjusted to the darkness and the sheer quantity of stars became apparent. With the wind flowing around us, the moonlight reflecting on the water, and stars shining brightly on the Pacific Ocean, it truly felt freeing.

August 11th, 2025

Rolling over the waves in darkness, this morning was quiet across the ship at the start of my morning shift—just a couple of students and ambassadors scattered about the Main Lab. I was told that Jason still wasn’t diving due to weather conditions and that there would be a reassessment of swell height and direction at first light. I spent the morning attempting to do some research for my project idea, which unfortunately led to some dead ends. In need of a morale boost, there was a box of paracord and knot-tying books tempting me on the student’s desk, so I decided I’d give it a whorl while I watched the light slowly intensify on the horizon in a beautiful orange and blue hue. During breakfast, an announcement was made that the Jason team would be ready to begin their dives of the day at around 0830.

We had Captain Derek lined up for our student meeting today, which was extremely interesting. Having grown up learning how to sail and taking some classes, I’ve been around different kinds of captains over the years, so I really enjoyed chatting with Captain Derek and getting to know his story since I hadn’t ever talked to a captain with his title before. I’ve known for a long time that captaining ships and spending so much time at sea tends to lead to an accumulation of some wild stories, so I asked the captain about one of the craziest stories he’s developed over the years. He talked about this one time near the Caribbean they came across a homemade raft occupied by four Cuban refugees who were out of food and water, wanted to get to the U.S., but had been stuck in an eddy for roughly sixteen days. He was able to work out the logistics of having them on board and coordinated a plan with the Coast Guard to intercept them before they got too close to shore. He emphasized how grateful they were for the help, hospitality, and beef tenderloin and lobster tail dinner they were treated to their first night aboard. Truly a heartwarming story and by far my favorite question to ask captains or those in similar lines of work.

This evening, I started my shift with a short Jason dive working the video photography. The goal of the dive was to flag the deep profiler mooring to be picked up in about a week or so by R/V Sally Ride. A sadness passed over me as the flag hovering just above the water’s surface connected to the buoy below slowly drifted away from the ship for later collection. The rest of the shift was filled with starting a new dive to replace a package on a shallow profiler that was earlier picked up on our way out to Axial Base. An exhausted funk has fallen over me today, so tonight, I will end the day with some laundry and a good night’s sleep, anticipating tomorrow’s activities.

August 10th, 2025

After waking up for my morning shift and realizing that we had just started our 20-hour transit, I was told I was able to go back to bed since there was little going on around the ship, which I took full advantage of. I didn’t wake back up until after lunch. I wandered up to the galley to see if I could claim some leftovers, which was when I pieced together why this transit was so much more tolerable than the last one. Instead of going dead into the wind, we were traveling perpendicular to the waves this time, offering a less intense rolling motion at a lower frequency. Even though I knew it was going to be a down day, I was extremely happy that I wouldn’t be confined to bed for the next 8 hours.

We got a tour of the engine room today, which was fascinating. The first engineer, Greg, gave us a summary of some of the equipment used to accomplish different things and how to manage all of them. From the four engines onboard, to the reverse osmosis water system, to the bow thruster, it was interesting to see how different they all were and the sheer amount of space they took up to service the whole ship. A wide mixture of sounds, smells, and temperatures greeted the group as we moved around in parts of the ship many of us hadn’t yet seen.

The rest of the day was filled with fun little activities to pass the time. The merch sale happened today which was very exciting. I hadn’t realized that all the shirts were designed by crew members, which made it even more special. The students were able to play some card game as well since none of us needed to do anything during shift. This was a nice time for us to step away from work and get to know each other more on a casual basis.

The waves have certainly picked up and it’s been entertaining to watch the ocean throughout the day. The water moves so differently out here, it’s beautiful. However, all the Jason dives were put on hold until the conditions calm a bit. While it was nice to have the day off, I am looking forward to getting back into the schedule.

This morning started with an unexpected complication to the anticipated day’s schedule. There was a plan to start a Jason dive right at the start of my morning shift, which I was really excited about. All was normal until Jason was swung out alongside the side of the ship about to be lowered into the water when all the screens in the van cut out and went dark. A simple “standby” turned into the realization that the jet way, the box that steps down the power to Jason from the ship, had experienced a ground fault. This repair started at around 0500 and lasted until a little before dinner. So, my morning shift quickly switched to brainstorming for my project and my evening shift was filled with the first Jason dive of the day. It was interesting to see the progression of this repair throughout the day. I already had a lot of respect for the varying teams aboard the ship but today increased that ten fold as everyone swiftly transitioned to troubleshooting, solving, and continuing through the day relatively unphased. That first dive today seemed extra special to watch since witnessing the team’s actions and the repair of the ship’s beloved ROV.

I had this realization today that we’re just sixty souls aboard this floating piece of metal with nothing in sight and nobody else to be seen. All living under the same conditions, individually working on different things to accomplish the same goal. It’s a simple thought but the idea of this extremely isolated, yet coherent community struck me today and I haven’t been able to stop pondering it. I’m very grateful that I’ve gotten to experience what that feels like.

We’ve been forecasted to see nine-foot swells in the next day or so, which will be interesting. I’m glad the seas have slowly eased us into the roughness, although I’m not sure I’ll be able to fully adjust to this amplified motion by the time the waves arrive. I’m excited to experience it, nervous about how I will feel during it.

August 8th, 2025

My first alarm this morning was accompanied by the realization that we were in transit again. I knew the transit was in the schedule, but was really hoping it would be over before the start of my shift. I decided to snooze my alarm a couple of times in hopes of waiting it out, leaning on the fact that I’d be able to get ready quickly. Sure enough, the ship approached station, and I rushed to gather my things for the day.

I saw that a shallow CTD cast was on the schedule and figured it would be for collecting more samples for typical measurements of dissolved oxygen, DIC, salinity, nutrients, and chlorophyll, but I was wrong. When we first got to the ship, I helped Lacie Levy, a graduate student at University of Washington (UW), get her equipment set up which comprised largely of two peristaltic pumps and many water canisters for managing samples. She’s studying metabolomics of single cell organisms in extreme environments. Back at the UW, she works with algae in polar environments, but has been intrigued by hydrothermal vents for a long time and plans to apply similar ideas of her previous work with different methods and from a very different environment on this trip. Today was the first day she began sampling from the CTD and Jason Niskin bottles with this setup, so my shift mates and I helped in whatever way possible. It was an intriguing process and a nice way to switch things up for a bit. I’ll be very interested in seeing how her data comes out and how it could potentially compare to some of her work and data from polar algae.

Just after breakfast, Jason landed pm the seafloor at the summit of Axial Seamount. We were about to see the first hydrothermal vents of this cruise, and my first sightings in real time. Of course, I’ve seen photos and videos of these vents before, and even those of past VISIONS cruises, but this was different, this was more. To think that the R/V Atlantis was ~1550 meters above what we were seeing on the screens through Jason was mind boggling. It’s moments like those that give me reassurance that I chose right, this is where I’m supposed to be.

With a smile gleaned across my face, I watched as Jason approached the first vent site, and I was speechless; I think most people in the van had no words regarding what we were seeing, at least for the newcomers. For the others, where this is just another day in the office, they seem to get a lot of entertainment and joy out of watching others experience this for the first time.

I was quickly losing energy after my shift, so I decided to watch the livestream from my berth. At one point, I noticed this slimy looking stringy matter on one of the wetmates, which piqued my interest. Later, I found out that it was filamentous bacteria. There have been whispers of collecting a sample once Jason surfaces and attempting to sequence or culture it. Who knows how it will behave in a laboratory setting without deep sea conditions, but it would be fascinating if something like that could be done. I’ve recently become really interested in genetics and barcoding, so this seems like an interesting opportunity to potentially explore that more.

My evening shift was something like my morning’s, with my time split between the control van and helping with Lacie’s samples. For the rest of the night, I soaked up as much time outside and in the van as possible since we start our 20-hour transit return trip to Slope Base tomorrow around lunch.

August 7, 2025

Immense relief filled me as soon as I noticed that the ship had stopped rising and falling with the waves it was fighting head-on during transit—we were on station. A Jason dive to the shallow profiler mooring, located at the base of Axial Seamount, started immediately and I popped into the van for a brief while to get away from my berth and get some fresh air. I then settled in for my typical three-hour rest before my morning shift, ecstatic that I would be able to get back in the groove again at 0400.

This morning’s shift was by far my favorite thus far. Given that there was only one other shift of ours that had a dive occurring, I was only able to gain experience with one of the two student stations in the van. This morning, I got to try the logging station for marking dive events. While I enjoyed the photo documentation style, I felt like I wasn’t as involved in the process as I wanted to be.

The logger’s job is to add descriptions and timestamps on the dive as it progresses by both watching the numerous monitors displaying camera footage and by cross-referencing the dive plan. Given that it had already been day four of the cruise and I hadn’t tried logging yet, I was very nervous to give it a try, out of fear of missing key points throughout the dive. However, I very quickly fell into a rhythm and really enjoyed it. I had been watching dives whenever I’ve been able to, but interacting with this activity in this way added a whole new dimension.

For today’s student meeting, we had a Q&A session with the galley chef, Ben. He shared his story and how his current position came to be. I found his current lifestyle very inspiring, with a 3-month-on and 3-month-off schedule, he spends a lot of his off time traveling around both domestically and internationally, with the only state he hasn’t visited being Hawaii (which he hopes to visit very soon)! It was also interesting to hear how a ship galley functions, both on a day-to-day basis, but also long-term during long voyages. Thank you

We then deployed the second deep-sea CTD, adorned with many decorated Styrofoam cups. This material has enough air in its pores/pockets that it will compress greatly at 2600 meters (deepest point of CTD cast) and will come back to the surface a small fraction of its original size. Another somewhat comical method of representing the changing conditions down the water column. While a little collapsed inwards and crinkled in spots, my cup made it back to the surface after a several hour journey. This was such a cool souvenir idea, I know I will cherish my cup that has been to the bottom of the ocean.

For the last portion of my shift, we started the last Jason dive before heading into the caldera tomorrow. This dive is estimated to take around six hours, with a short transit time to follow, then the first twelve-hour caldera dive of this year’s cruise. Since I wasn’t at a student station in the van, I was pulled away to help with labeling bottles and vials for future pH sampling, which offered a nice time to slow down for a bit and listen to some music while the sun’s light began to dull.

Normally I’d stay up for a bit after my evening shift to watch the livestream or hang out in the van, but for tonight, I think I will be maximizing my rest in anticipation of being completely enamored during tomorrow’s caldera dive and not wanting to leave to take a nap.

August 6, 2025: Disclaimer: talk of seasickness

I would be lying if I said I remember the forces that act on one’s body in situations like an elevator or airplane turbulence when it feels like everything suddenly becomes heavier or lighter. Changes in gravitational forces, normal forces, inertial maybe, I took general physics several years ago now. All I know is that I woke up to feeling like I was levitating, then suddenly being slammed down onto my bed every 5 seconds or so. I slept well, so I was chalking this confusing experience up to the wind picking up in the middle of the night while we were still on station, wrapping up the last bits of Jason’s recovery.

I may be beginning to understand why the “Board O’ Lies” is called such as we were posted to leave for Axial Base just after breakfast; however, upon reaching the Main Lab for my shift, it became obvious that we were already on our way. I was about thirty minutes early for my shift and was unfortunately never able to start it.

Since it was 0300, it was dark, offering no horizon to stare at in hopes of taming the quickly approaching sea sickness. The Main Lab was hot, and my stomach was empty. I was asking for it. I rushed up to the mess hall, filled a cup with cereal, rushed back down to my berth, and laid down with my little snack, hoping it would help the situation. It did, and my rest time turned into a nap time. I felt mountains better when I woke up and figured I’d once again attempt to be productive in the Main Lab, but this turned into another failure.

At that point, despite my wishes, I had decided that it would probably be best if I spent the rest of the 20-hour transit time in my berth. Sometimes, sea sickness medicine just won’t cut it and while I haven’t gotten fully sick, it has been a dance. I’m grateful that I’m able to escape it at all. This was what I was most nervous about for this journey, and no matter how much I wish I could avoid it, I suppose it’s part of the deal. It’s a sacrifice worth making as I’m growing increasingly excited to see Axial by the hour while trying to avoid thinking about how we will be doing this again for our return trip. While today was a bit of a wash for me, I’m hoping tomorrow offers calmer seas as we approach station so that I’m able to get back to learning this wonderful science.

August 5, 2025

A restless three-hour rest gave way to 0300, which was when my first alarm went off. I slowly crawled out of bed, realizing that this shift schedule would take some getting used to. I was greeted in the Main Lab by near silence as I began orienting myself about what was going on and what I would likely be doing for my shift. A monitor fixed to the wall revealed the familiar underwater site of one of Jason’s cameras, hinting that I would start my early morning in the control van. The five steps outside from the main cabin of the ship to the van door were relatively chilly, but it served as a nice and efficient way to fully wake and gear up for what I was to walk into in the van. After around five minutes of getting acquainted with the current dive, the cameras on Jason indicated that it had just breached the surface and was placed back on deck. This was when I realized that the 0500 steam to Slope Base posted on the “Board o’ Lies” that I had checked prior to heading to the van was underway. With that, we quickly transitioned to more Niskin bottle sampling, but from a bottle attached to Jason this time. It was fascinating to think that we were handling water from hundreds of meters deep in the ocean, with properties likely differing from the water we are all able to observe at the surface—what a privilege and an honor.

I am extremely grateful that my shifts are from 0400-0800 and 1600-2000. This means that I will almost always be up and working for both sunset and sunrise. While I may not be able to see every light show, my chances are higher than if I were asleep. I’ve been told these passings of the sun are always unforgettable and magical, and I can’t wait to experience them for myself. For the sunrise this morning, while gazing to the east and listening to the movement of the ocean water, I had the realization that for the first time in my life, I couldn’t see land.

After coming up on station, I was able to utilize yesterday’s CTD training during my first CTD deployment. Tasked with one of the taglines, I shared responsibility with another student in keeping the instrument relatively laterally stable as it was lowered into the water by the winch. I had only just watched this be performed previously, so it was rewarding to get to be a part of the deployment process for the first time today.

As the conditions slowly became sportier, my shifts for today grew more mellow compared to yesterday’s, offering a nice pace as I readjusted to the heightened movement. Following our first student meeting, my evening shift started with watching the CTD descend to the station’s seafloor at almost 2900 meters at Slope Base. The ascent back to the surface took about an hour and half, which was a thought provoking and useful metric to represent just how deep the instrument had gone. Bringing 24 Niskin bottles full of bottom water, the CTD was finally recovered and provided its various profiles to the science team. After filling two carboys with the Niskin water, the rest of the water was dumped onto the ship’s deck, making me wonder about the monetary value of the water that was quickly rushing off the side of the ship and the price of the corresponding time it took to obtain this water. Preparing for the cruise’s first ROV-assisted journey to the true seafloor, the carboys were rushed to Jason to provide ballast for its long deployment.

The 18 chlorophyll samples that had accumulated over the last 24 hours or so were begging for processing, which led me to my next shift task. Using a vacuum pump system, each sample was passed through a filter which was then collected, folded, placed in acetone, and stored in the refrigerator until further processing can happen on shore. The consistent rocking of the ship in the 13-knot wind-driven swells coupled with the dark lit lab created a soothing scene for this fascinating, yet repetitive duty.

All the students have been warned of our 20-hour transit to Axial Base tomorrow, likely beginning after breakfast. The rapid increase in distance from shore may lead to some of the largest swells we’ve seen yet, so we’re all triple-checking our equipment tie-downs and hoping the sea sickness stays subtle. However, I am currently waiting in eager anticipation of Jason touching bottom in several hours as I stare at the live streamed video on my computer while preparing for my night’s rest.

August 4, 2025

We arrived at the Port of Newport yesterday (8/3) after a long, but lovely six-hour drive south from Seattle. That trip was a wonderful first interaction with a subset of scientists and fellow students who were all very excited about either embarking on their first ocean-going journey or continuing their sea time logs. I lost my breath for a moment as we descended the slight hill into port and saw R/V Atlantis for the first time through the breaks in the trees. It all suddenly felt real, and it was hard to believe that that would be my home for the next two weeks. We soon began unloading our luggage and gear onto the ship, which was when the scale of it all set in. I had been on large ships in ports before; however, after seeing so many pictures of this specific ship, Jason, and other such equipment, it almost felt strange seeing it all in person.

Everything was much larger than I was expecting. After an evening exploring both the ship and the dining scene of the town of Newport, I settled in for the night with some delicious Thai food in my stomach after a long day.

Following a very restful night of sleep, I woke up to an amazing breakfast which included some of the best pancakes I’ve ever had. We then mustered in the main lab for our safety meeting where we tried on some incredibly awkward, but very sturdy life jackets and full-body immersion suits in case of an abandon ship situation. Without warning and before I knew it, the distance between my lab bench in the main lab and the view of the dock through a starboard side portlight was growing. We made our way to the deck on the bow as we crossed under the famous Newport bridge, steamed through the channel, and out into the open Northern Pacific Ocean.

Following lunch and a couple of steaming hours, we had an orientation with the Jason team where we were given a tour of the machine, the control van, and our logging/documenting responsibilities. It was fascinating having one of Jason’s pilots explain the components of the remotely operated vehicle (ROV), their function, and/or purpose. As I was staring at the mineral oil surrounding delicate wires encased in a housing box, I couldn’t help but notice the intention that must’ve been behind each decision during its construction. It was strange to think that I was currently looking at something that would soon be and historically has been on the seafloor for long periods of time. Walking into the control van, where the manipulation of benthic equipment is conducted and observed, was like no other feeling I’ve ever experienced. Monitors line the wall of the dual-joined shipping containers which display various views from cameras on the ship and Jason, with joysticks and other computers occupying the table space, used for controlling and monitoring ROV activities. Wonder, excitement, and pride immediately streamed through me.