August 28, 2025

Despite having written every day, it feels strangely grim to sit down, on my last day aboard the ship, and try to sum it all up. I’m unsure where to start: I can say that in these past ten days I’ve had countless mugs of black coffee, downed dozens of different pills, finished at least two crosswords a day… my blood practically flows neon with Gatorade by now. I can measure by these metrics, but I can’t begin to inventory the things I’ve learned- not only about doing science, but about how to be around others.

I was struck every day by the kindness and humor and patience of the people on this ship, the way they handle themselves while working towards a collective goal, even when exhausted and sleep deprived and, doubtlessly, socially drained. I can also say that I’ve seen, heard, and felt things more beautiful than I could ever have imagined, and that every second of my time on this vessel has been precious, and utterly irreplaceable.

A lesser point, but one that matters very much to me: I drew every day for the past ten days, and most days I drew for hours at a time. I don’t remember the last time I could say that. Even if at first it felt stiff and forced, I am awash in gratitude and relief at regaining this simple but integral part of my life. I have always wanted to go to sea and have always loved the ocean and all its residents, but I could not have known how transformative this short time could be.

We got a dose of dreamlike golden sunsets, endless sparkling sea, and leaping dolphins; we also got swells and heavy fog, and I certainly got more than my fill of seasickness and malaise. A well-rounded experience, I would say, although I’d shudder to repeat some of it if I wasn’t armed with electrolyte tablets and anti-nausea patches. I wouldn’t trade any of it for the world.

Above all, this experience cemented my love for the ocean and my determination to find a place for myself in the world of marine science: to overcome the pervasive impostor syndrome which hooks its claws into me both in the field and in the classroom. I am so grateful to have had the chance to do this, and I can only hope for the privilege of staying in touch with VISIONS team, however that may be.

August 27, 2025

We were up late last night, burning the midnight oil so to speak (actually, it was ethanol, and we were doing worm stuff). Mason and I, having plenty of time on our hands, volunteered to help Andrew with his annelid-related research, spending what might have been 20 minutes or 2 hours switching the preservative for his hundreds of samples. At first, Mason was carefully pipetting out the waste ethanol, yellowed with worm particulates, and handing me the drained tubes; by the time we’d made it halfway through the case of samples, we were unceremoniously dumping out the used stuff, which went much quicker, and handling the worms like total pros.

In lulls between tasks, I made a valiant effort at reading the glossary to Andrew’s annelid handbook, an enormous and dense volume with a completely unusable index. This didn’t go so well, since the definition for each term also referenced at least a dozen other terms well out of my wheelhouse. I only succeeded at confusing myself more: invertebrates are a total mystery to me, as fascinating as they are. Once all the worm samples were cleansed and replenished and the room reeked of ethanol, we took a cereal break, and before I knew it, it was 2 in the morning. I was wired from migraine meds and an excess of sleep the night before, and I lay awake until almost 5 in the morning thinking about everything and nothing, and stuck halfway through a crossword.

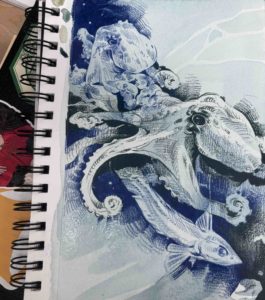

Today was another slow, companionable day in the lab, and I spent a good deal of time sketching octopus for Deb (her favorite). I’ve always avoided drawing octopus, fearing I wouldn’t be able to capture them in all their soft-bodied glory; after all, they’re such beautiful and intelligent creatures, I would feel guilty misrepresenting them. The sketch turned out alright when I reminded myself to draw faster and pull the lines with my whole arm, not just in little movements from the wrist. I broke from my cephalopod meditations to race out onto the deck, where three or four fin whales were dipping gracefully just off the bow. Their shining bodies were stark against the gray swell, reflecting the faded sky. Even the water itself had a nebulous quality to it, a way of warping the fog’s glow into arcs and dapples which mesmerized me.

All day I was circling, thinking of what I should do with my last few hours at sea: what could I have missed? I had innumerable questions still unanswered. There were still so many sensors and acronyms that I hadn’t managed to figure out, though I put some of these to rest later in the day, poring over an enormous diagram of the cabled array and picking Deb’s brain. I’d arrived at the point in the cruise where I was missing solid ground: I wanted to buy flowers for my kitchen, sleep in my own bed, and more than anything, I missed my people back home. Still, with the sea stretching out in all directions, I’m never short on gratitude for my time here. Oh, and I should mention: later in the night, we sighted a blue shark which swum right up to poke its nose at the Jason camera. Once I see one up close and in person- then I can die happy.

August 26, 2025

I stayed down for hours this morning, drifting in and out of vivid dreams I was reluctant to break from. I was blissfully free of nausea for the first time in days, cushioned in the perfect darkness of my cabin, and as if to mock me, every time I woke the swells picked up again or we began another short transit… I took this as a sign from the beyond to keep on sleeping. On the other hand, every minute spent in my bunk was a minute wasted, and I could feel the clock ticking and ticking with just a few short days left on the sea. Time is so precious here. Every moment is another chance to learn from someone, or get my hands on some instrument- I’m intensely grateful for even the most banal tasks and offhand conversations.

So I forced myself up, and as if to reward me and remind me what I was missing, I stepped out onto the deck to see a whale’s fin flash gracefully, disappearing just a few feet from the side of the vessel. That was the last we saw of the whale, but it was enough to ground me. I set to work furiously hydrating and consuming as much salt as I could get, diligently meeting my body’s tedious checklist of needs. During another short transit spent on the side deck, I was rewarded again when I noticed a plume of blood staining the boiling surf; a tiny juvenile shark was thrashing with all its might, whipping furiously back and forth to tear a chunk from the unfortunate fish. I knew we were nearing the coast when a gull made an appearance, and then a fishing boat emerged from the fog, bobbing in our wake.

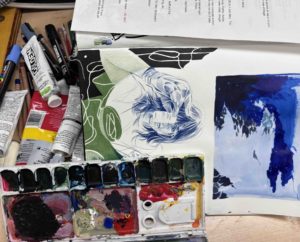

It was uncertain whether the science team would be able to deploy the new Benthic Experiment Package today, as this 3000-pound treasure box of sensors needed calm seas for deployment. Too heavy to be ferried to depth by the ROV, the BEP has to be deployed by hand- by many hands- off the ship’s side, and these operations can be dangerous in foul weather. It turned out to be a bust. The fog was only thickening, drifting in to blanket us until the world was gray and the air was heavy, the horizon long ago vanished into the soft sky. So we spent the afternoon in the lab, some working, some gaming, others presumably catching up on precious sleep. I was invited to join Léo and Ada at their painting station, where we passed the time mainly in companionable silence.

For what felt like the first time in months, I was content with a pencil in hand, and my mind was quiet and free from the buzzing spiral of anxiety and doubt. This is what I used to love about this, I remembered- this is the reason I do this in the first place! This feeling is the reason behind the countless paychecks I’ve spent at the art store, the countless hours and pages and, after all, the reason for living (I think). I can’t imagine a better way to spend a day.

August 25, 2025

I was so comatose this morning that I had to be woken up to help with our CTD recovery; unshowered, fuzzy-brained, and squinting under a blinding gray sky, I was hastily instructed on how to hook a line to the rosette’s frame. I pulled this off a little gracelessly, but succeeded at not breaking the thing, and only had to be hollered at a few times. My head was pounding, but I crammed a pastry in my face and made myself useful as we sampled the Niskin bottles for nutrients and chlorophyll. Lowly undergrads don’t get to touch the oxygen or DIC bottles, and for good reason – they’re easy to compromise, and the DIC samples, collected in repurposed beer bottles, require a hefty dose of mercuric chloride to kill off anything surviving from the Niskin.

After a much-needed rinse, I came upstairs just in time to learn to deploy the next CTD, a deep cast that would also carry our precious Styrofoam cups down to a depth of almost 3000 meters, where they’d be adorably crushed by the pressure. I tied my first bowline (baby steps, I know), and did my best to hold the CTD line steady as the crane slowly lowered it into the water. The rest of the morning was consumed with Niskin sampling, followed by a short transit, which I spent in my new favorite spot on the port-side deck, crouched with my eyes glued to the horizon. I’d evaded seasickness again, but the dull ache behind my eyes which had been tolerable for the last few days just seemed to worsen by the hour.

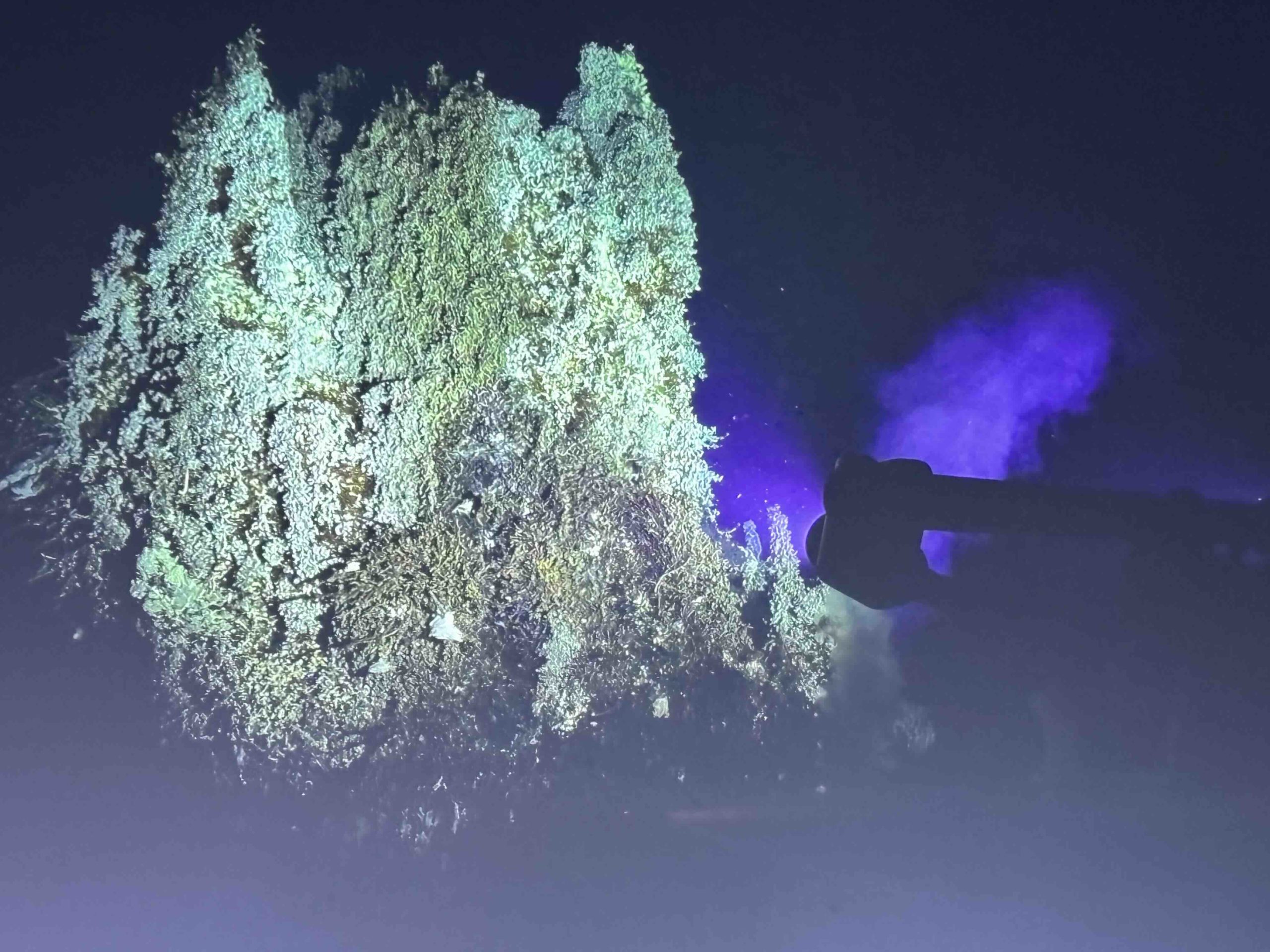

I had to hold out, I told myself. Tonight’s dive was another exciting one, a photo survey of the Southern Hydrate Ridge methane seep site populated by hundreds of snails, and its 60-meter-high Pinnacle, which promised to be stunning. I knocked back more aspirin and took up a spot in the back of the ROV van; this was a much shallower dive, and we reached the bottom around 700 meters as opposed to the usual 1500 meters, which was covered in soft corals, crabs, and rockfish dressed in jolly red and orange scales.

There was so much more life here, the seafloor glinting with white clams, which occasionally cracked their shells to expose ruddy pinkish tissues- I was thrilled to see hagfish, some of my favorite fishes, weaving in and out of drill holes like craters in the sediment, and pressing into crevices to hide from the lights. Every now and then, the camera would capture a blood red ctenophore passing by, the light refracting in delicate rainbows off its oscillating cilia. We even sighted a few molting crabs, one of whom was suffering a vicious slow-motion attack from one of its peers in its moment of weakness.

I survived about two hours before the monitor lights, boring into my skull like railroad spikes, became too much. When my vision started to blink out in spots, I finally put two and two together: of course, this was a migraine. I hadn’t had one in years, but now everything made sense. The pain from the fluorescent lab lights, which I’d attributed to my normal sensory peculiarities, the nausea which I’d thought was seasickness… etc. Ella kindly showed me to a cooler full of Gatorade, and I sequestered myself in my pitch black room with a crossword to keep me company.

August 24, 2025

This morning’s dive was one I’ll never forget: so eventful that before I’d even been on shift for half an hour- and before Jason even reached the seafloor- the van was packed with scientists waiting to watch the show. In between log entries, I was hurriedly texting my friends and family to tune in to the live stream. Today we were visiting Skadi, a hydrothermally active area aptly named after the Norse goddess of winter and hunting. Three months following the 2011 eruption, billions of microbes and white flocculant material streamed from a collapsed area at this site, fondly called a snow blower. Our only objective was to conduct a photo-video survey of the site. In other words, all I needed to do was sit back and take note of the breathtaking geological formations, logging the wealth of bacterial mat, thriving tubeworm bushes, and the occasional sedentary blob sculpins, which settle themselves like grumpy, whiskered oldsters on the rocks.

There was some contention over the background music for this remarkable dive, but the Chief Scientist’s word is gold, and Deb chose the soundtrack to Bladerunner (the original 1982 movie, of course). It was fitting: the sparkling synths and sweeping chords made the underwater landscape feel like a sci-fi film.

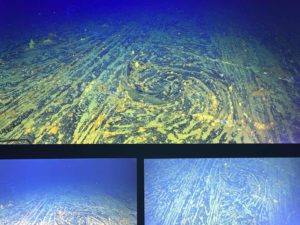

Jason was following a hardened lava river like an abandoned train track through the dark water. Bacterial mat lining the river’s ridged surface made it seem to glow with flecks of gold, but the true showstoppers were the collapsed basins: pillars and arches of volcanic rock rising from the seafloor, piles of basalt rubble- through the broad skylights, we could see the silvering shimmer of hydrothermal flow. Any layperson would’ve thought this to be an ancient ruin or temple, buried beneath almost a mile of water. A geologist, however, would tell you that these structures are born when lava flow, encountering freezing seawater, solidifies and forms a hardened ceiling. As the remaining lava steadily escapes the chamber, a series of “bathtub rings” are left behind, and with nothing to support it, the ceiling often crumbles. The pillars, Deb explained, are the result of pipe-like spaces in the lava flow formed by water vapor as the 1200°C flow covers the water-saturated seafloor. After this morning, I might be a convert to the geological sect.

I spent the remainder of the day awestruck, staring into the gray horizon and watching the Atlantis cleave through whitecapped waves. I was hopped up on a hefty cocktail of seasickness meds, determined not to repeat my fateful first day at sea as we began another 19-hour transit to our next site. We were treated to a tour of the engine room, where I discovered just how complex the guts of this vessel are; the Atlantis has two of everything, I learned. “In case anything breaks down”, our guide clarified, and I thought of how glad I was to live in the 21st century, in a time when dying at sea is no longer a serious concern. Well, mostly.

Once I was sure that I’d traded seasickness for a splitting medicinal headache, I buckled down and spent several hours covering a Styrofoam cup in sharpie drawings. It seems ironic that a team of environmental scientists would have so much Styrofoam around, but these cups serve an important purpose. They’ll be sent down with one of the later dives, and will shrink into tiny personalized souvenirs under the mountainous pressure at depth. I dedicated this cup to my housemates, whom I miss terribly, and it has all our favorite things: our cat, a jar of laoganma chili crisp, the extinct fearsome predatory shrimp Anomalocaris, and more.

August 23, 2025

My morning started with a jolt: if my several alarms went off, then I’d slept through them. It was now 8:01 a.m., and I was shamefully late to my shift. As if to punish me for this infraction, I woke to the most atrocious neck pain I’ve ever experienced, the likes of which I thought were unique to international flights and serious head injuries. Who knew I could do such gruesome damage just by sleeping. Soothed slightly by a handful of Advil and a jam danish, I strapped in for another photo survey – this time, I at least had some seafloor to stare at. Still, any complaints I could have on the Atlantis are sweetened by a quick glance out a porthole window. It’s hard to be unhappy for long when I remember how lucky I am to be out here, how precious this time is, and how much I’ve already learned just from watching and listening from the sidelines.

After lunch I returned to my painting purgatory, steadily filling the background with deep indigo that made the chimneys seem to stand imposing against a starry night sky. My thoughts kept returning to a conversation I’d had late last night, in which my watch partner asked me offhand if I wanted to be a research scientist. I had no idea, and still don’t. By now, only a few quarters away from graduating with a bachelor’s in marine biology, I should at least have a tentative answer to this very simple question.

But it’s a hard question, isn’t it? It implies a chain of other questions: is there a place for me in research- in science? Jobs and funding are drying up, so do I have what it takes to succeed in an increasingly competitive field? Fundamentally, am I good enough, smart and committed enough for this? But at the same time, the simplest and most important question is still if I want to be a research scientist. The only approach I can see is to throw myself into this work with as much optimism as I can muster, and let the question answer itself.

After a wonderful talk about deep sea biology given by Co-Chief scientist Mike and a little work wrapping cables, my motion sickness returned with a vengeance when the wind picked up. It was too much for me, and I had to bail out of my watch – but the sunset was breathtaking to watch as I crouched in fetal position on the deck, nibbling at a chunk of fantastic homemade sourdough. Luckily, I wasn’t shirking my duties too much: we were ahead of schedule, and the decision had been made to pause dive operations until morning and let the science team and Jason pilots get some rest. My nausea even subsided in time to get a tour of the worm-sorting operation taking place in the analytical lab, which consisted of an assortment of large buckets filled with murky liquid. This one was for palm worms shucked from their casings, that one for worms still unsorted… a jar here for scale worms awaiting their tragic end, the one next to it containing a smaller species never found at Axial before, and so on. I ended the night laid out on my back on the upper deck again, listening to the whitecaps kiss the ship’s hull and counting shooting stars. How lucky am I to be in such a beautiful place, and in such good company.

August 22, 2025

Today was a sleepy day aboard the Atlantis (at least for me, its least busy passenger). The morning shift felt unremarkable, as the Jason cam took hours of footage of hazy, particle-flecked twilight. I logged little more than the start and end of each transect line, and the occasional jelly drifting through the frame; the more exciting work was behind the scenes, as these were acoustic imaging surveys using the multibeam fixed to the back of the vehicle. Jason passed steadily back and forth, tracing a grid pattern just meters above each vent, letting the sonar do the work of imaging the hydrothermal plumes which rise through the water column, cooling gradually as they mix with the frigid seawater.

In my seat behind the logging monitor, I imagined what it would feel like to be able to dive this deep, to plunge into pitch black water and be surrounded by this microbial and planktonic soup, brushing past the soft housings of salps and larvaceans. By this point, I was beginning to feel the compounding sleep deprivation. I lamented having missed last night’s “worm massacre”, as the science team has been calling it: I’d hoped to stay up to help process some of the biological samples taken from a rich, blooming tubeworm bush on last night’s dive, but had opted to get a few hours of sleep instead. When I woke this morning, my cabinmate Ada was just returning from this all-night worm party, so it seemed like I made the sane choice.

Still, as a marine biologist at heart, I was sore about missing the chance to see these incredible creatures up close. Some of the tubeworms, recovered from the vent in a bizarre bouquet of carbonate casings like otherworldly spaghetti, had been almost as tall as me! I’d been informed by Andrew, one of our resident worm experts, that these hydrothermal colonizers can display up to 40 morphotypes within just one species depending on where they’re found in proximity to the flow. These enormous specimens were the “fat and happy” morphotype.

In between tasks, I’m working now on a small painting of the chimney called “Mushroom”. It’s certainly a challenge: I’m stuck obsessing about the delicate gradations in color on the bleached surface of the vent’s tubeworm colony, the quality of the water, the cloudy finish of the plume billowing from the chimney’s base. On top of it all, I’m really not much of a painter, never having truly gotten a grip on color theory or how to handle acrylics. Maybe that’s a good thing, I keep telling myself. If anything, this is the place to experiment- to throw habit out the window and practice the skills I feel most uncertain about. Still, I’m determined to pick up a pencil or a brush every day.

August 21, 2025

My caffeine intake on the ship has been steadily increasing by the day: today I’ve had two cups of coffee on my morning shift, one monster energy, and am halfway through a sizeable iced coffee. Probably there will be more to come. In my defense, my brain and body can’t seem to agree on whether I should be awake or not, with my body flagging and my brain egging me on, saying “come on, there’s more to see! There are more questions to ask!” And what if I miss something? Today, for instance, I thought I might nap after my morning watch, but luckily a fellow student grabbed me to help with processing RAS samples before I could make it to my bunk.

But I should backtrack: in the late morning, just as the watch was beginning to drag on, two fin whales were sighted just next to the ship and we all rushed outside to watch them surface, puffing clouds of sea spray into the bright sky. Maybe they were curious about the Jason cable, or the ship’s low humming below the water, but we were graced with their presence for some time as they steadily traversed the Atlantis. Not only that, but I spotted a baby blue shark just beneath the surface. The miniature fins and tail made it look like an adorable rubber figurine rather than a fearsome predator, so tiny and fragile I could barely believe it was real.

We passed the later part of the afternoon working an efficient assembly line and chatting idly in between samples. Each of the 49 water samples, which we’d pulled from the RAS apparatus on Tuesday, needed to be weighed and subsampled into gastight bags; the remaining vent water was passed to another set of hands to be divided into a plastic bottle for pH testing and two smaller vials for hydrogen sulfide testing. Around bag #15, we had the process down cold. This process didn’t feel too different from my day job working in a café kitchen, just with kimwipes and pipettors instead of rags and milk pitchers. And, of course, I was in excellent company.

I ended the night with another trip to the deck to stargaze. It seems to be becoming a ritual. After a night shift in the van, it’s hard to turn away and face the blinding lights of the ship galley when the milky way is right there waiting for me. Maybe tomorrow I’ll manage to wake up in time to make it to breakfast.

August 20th, 2025

Science stops for nobody, with an occasional exception for dolphins. The sun set last night over a glassy sea, swells rolling like fine silk stretched in every direction, and my second shift of the day had just begun when the pod appeared. I was standing at the railing outside the Jason van in a moment of silence before the winch started rumbling, letting down the cable for another dive. It’s the quiet that gets me, I think- that makes it impossible not to think of the vastness of all of this, of just how small you are as you stand, held down only by the great mass of this planet- how young and stupid you are in comparison with the ocean, and beneath it, the crust, the mantle, wrinkled and faulted and still, after all this time, changing shape. Joni Mitchell calls it a “marbled bowling ball”, which feels about right; it’s easy to believe the world is just one endless ocean out here.

When the dolphins were spotted, I was given the OK to abandon my post in the ROV van and watch them, an offer I happily accepted. The science team flocked to the bow, hurrying to grab cameras and capture the show, as the dolphins swam in twos, threes, fours, breaching the surface and leaping in perfect synchrony. A few seemed to be jumping just to see how high they could go, splashing gleefully back into the water headfirst and vanishing again with a whip of their tails. We spent half an hour like this, spirits high, smiles and camera lenses glinting as the light turned golden, then rosy, then softened to a sleepy lilac haze. This may be the best thing I’ve ever seen, I thought, and tried my best not to drop my phone overboard. The pod vanished the moment the sun disappeared past the horizon. I don’t remember dreaming of dolphins, but I woke up exhausted and content.

This morning’s dive took us to a site on the Eastern Caldera where the Jason team was tasked with recovering a prototype instrument- the “KRILL” platform- and returning the HD camera to its usual spot, where it keeps watch over a vent called Mushroom. When I arrived to start my shift, the van was packed and Jason’s camera was trained on another chimney, Inferno, surveying the site. This vent was rich with tube worm colonies and bellowing black smoke, the worms’ star-shaped heads waving merrily from a thick frosting of bacterial mat. One side of the chimney almost resembled a unicorn’s head, someone pointed out.

After this, the rest of the day was slow and sleepy, with little to do and plenty of time for me to sketch. I nervously churned out a quick drawing of myself taking temperature measurements from Monday’s CTD cast, then squandered the rest of this precious time by filling the bottom of the page with a jumble of overcomplicated arcs and lines in negative space. I was hoping to capture the feeling of being surrounded by camera lenses and endless thickets of cabled plugs, but I came away thoroughly dissatisfied and disappointed. I have to remind myself that this is part of the process, that I’ve felt this before, and it won’t prevent me from creating work I’m happy with tomorrow or the next day. Drawing is like science in many ways, but in this case, being technical and procedural, checking every box, and filling every inch of space won’t help me. I ended the night on the deck, lying on my back and watching shooting stars cross the gauzy line of the milky way.

August 19, 2025

I should know better by now: there is no “getting ahead” on sleep. Sleep, at least for me, is a boundless quantity, and a ceaseless obligation. I have always been a champion sleeper (and maybe even a narcoleptic, though I refuse to get it looked at), so it should’ve come as no surprise that it was almost impossible to drag myself out of bed this morning, even after a full seven hours. I dream differently at sea, and the images behind my eyes are far more lucid and surreal, the storylines more defined. It reminds me of dreaming as a child, the feeling of waking having learned something new, having set eyes on some bizarre scene for the very first time. In any case, I nearly slept through both of my alarms in blissful hibernation and thankfully woke, half an hour late, to the sound of my lovely bunkmate Ada shutting a drawer.

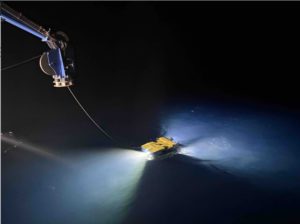

I made it to the van at 8, just in time to start my shift logging the ROV’s progress on the latest Jason dive. My shiftmate and I watched in companionable silence as the ROV sank again, 1500 meters down to the ridged basalt seafloor, a journey marked by the occasional red shrimp or jelly dancing across the frame. This dive was dedicated to swapping out a seafloor camera at the International District Hydrothermal Field and removing a TRHPH probe: a sensor measuring the temperature and resistivity of the scalding vent fluid which flows from the oceanic crust, and forms mineral-rich plumes at hydrothermal sites. The probe, now grown over by sulfide and into the side of a chimney called Escargot, was no longer collecting usable data. With a bit of jostling, the ROV pilots pulled the probe loose, sending a flood of super-heated fluid into the surrounding water, like some enormous alien tea kettle.

Seeing the pilots at work is like nothing else; the ROV is handled with such care and consideration- many times, I nearly neglected to log the latest of its movements, entranced in this delicate game of “Operation”. It’s like watching an open-heart surgery, performed perfectly, by a drone equipped with two metal forks. And the surgeon, of course, is calling in to direct the show from outer space.

Once relieved of my shift, I rushed to the deck to help with the RAS (Remote Access Sampler) apparatus which Jason had recovered from the seafloor, a process which was easy as pie with six pairs of hands to help log, label, and store the 50 samples. We worked like a well-oiled machine, flies buzzing incessantly around us, with Lady Gaga’s dulcet tones on the speaker. And later in the day, between restless trips to the upper decks, I managed to sketch a portrait of Ada, smiling and holding up a fresh sample bottle. It’s hard to draw nitrile gloves. This wasn’t something I envisioned being a challenge of learning to draw again at sea, but they’re a serious hassle: too much contrast and they look slick and shiny, and too little? You lose depth of form and any chance at that matte, almost grainy texture. Not only that, but Ada’s favorite color is purple (like her hair) and I didn’t bring any purple pencils at all.

August 18, 2025

After yesterday passed in a haze of seasickness, I surfaced this morning from a Dramamine-induced coma and managed to drag myself into the shower. Feeling restored, if a bit woozy, I found my way to the galley to poke at some dairy-free pizza, which Ben, one of the chefs, had kindly put aside for me. I was determined to get back on the horse and make myself useful. Although I’d already missed the CTD (conductivity/temperature/depth instrument) deployment and training, I made it to the CTD recovery in time to help with collecting samples from the Niskin bottles that make up the “rosette” of this instrument.

I was one of four or five others helping with this process, and although I didn’t get to handle the extremely toxic reagents used to test dissolved oxygen, I was very content to take temperature measurements and take over logging which samples were matched to each Niskin bottle.

We paused the process all at once for a dolphin break: a pod of Atlantic white-sided dolphins had appeared, jumping the waves in groups and jetting along just next to the ship. It had been years since I’d had the pleasure of seeing dolphins, and all my grumbling about the extra attention allotted to charismatic megafauna went out the window when I spotted this pod. They were absolutely beautiful.

In the midst of helping with the CTD samples, I was pulled away to my shift in the ROV van, where the Jason crew was deploying the vehicle for its first dive on Leg 2. My first glimpse of the van was incredibly exciting, although I’m sure the thrill will subside after a few shifts: it’s pitch dark in the van, and monitors line the walls, displaying the ROV footage as it descends through the water. The video is eerily beautiful, the depths glowing blue, with drifting particles illuminated like fireflies by the headlights. After a quick bit of training, I signed off my shift as the ROV continued its descent.

Today, though, I did manage to draw: a quick sketch of my friend Léo as they worked with the Niskin bottles on the CTD rosette. I’ve grown much more accustomed to the gentle rocking of the vessel, but still a few lines went askew with an unexpected lurch of the boat. It made me almost nostalgic for days of drawing in the backseat of my parent’s car on road trips, despite a bit of irritation with my linework. I still feel a bit stuck, and very out of practice, almost as if I’ve forgotten how to properly hold a pencil. Still, a final sweet discovery made the day: Redbull in the communal science fridge, so I can fully indulge my caffeine addiction!

August 17, 2025

This morning, the Atlantis left port at 8:30 am to sail out to Axial Seamount. Scientists gathered after breakfast to watch its departure, the waves folding in layers of frothy lace around the prow as the ship cleared the harbor. As we passed the gate of sandy dunes, the jellies appeared; as if out of nowhere, they drifted in the dark water by the hundreds. There must’ve been a recent plankton bloom, we noted, since these were sea nettles, usually seen in much smaller numbers. To me, they seemed to be dancing or playing in the wake, and I felt the wonder of being a child pressed against the aquarium glass again. I found myself wishing I could jump in and join them – a feeling that dampened when I was informed that sea nettles can dole out a nasty sting.

We grabbed hats and long-sleeved shirts when the ship’s alarm sounded, signaling that the safety drills were starting; this was when trouble started for me, after all my talk of never getting seasick. I didn’t even make it halfway through the briefing before I had to run out of the drill. I spent the rest of the day crouched in the head or curled up on my side on the floor of my berth, with periodic visits from the science crew to make sure I was still kicking. At some point, I managed to haul myself above deck, where things improved significantly for me, and I slept off and on next to the Jason ROV, popping as much Dramamine as I could keep down and keeping my eyes on the horizon.

I had hoped to draw today, to start taking a symbolic icepick to the glacier that’s frozen over my creative efforts for the past several months. Instead, I set smaller goals: eat a cracker, drink some diluted pink lemonade, and survive the transit. Maybe my time sprawled like roadkill on the rear deck did me some good, though, because I began thinking seriously about what I want to get out of this time at sea with so many brilliant- and, as I found out, very kind- scientists. Of course, I want to know how everything works aboard the Atlantis and be as helpful as I can. More than that though, I thought, I want to know what these people love about the work that they do.

I want to know how they cope with doubts about their research and their goals (if they every doubt), I want to hear about their frustrations, and the hopes that keep them going. Leading up to the voyage, I was constantly preoccupied with the idea that I would waste this precious and rare opportunity, that I wouldn’t get everything out of it that I possibly could. Now that I’m aboard, this seems like an impossibility. Even bent over a bucket, I was happy to see the ocean stretching out in all directions, and it was a joy to know how lucky I am to be even a small piece of this incredible team.